The Anchoring Bias

Why first impressions matter

When COVID-19 was first reported in early 2020, not much was known about the disease. It was a virus-borne respiratory illness, featuring flu-like symptoms such as fever, cough, aches, and shortness of breath. Early estimates of its case fatality rate (CFR) were lower than SARS and MERS, and its rate of spread roughly the same as the flu. It was generally assumed that transmission was primarily through respiratory droplets, and possibly direct contact, as is the case for many other common respiratory diseases. Doesn’t sound so bad, does it?

Is COVID-19 “like the flu” or “like Ebola”?

Comparing COVID-19 to the flu indeed “anchored” many to the idea that COVID-19 is “no big deal”, despite quickly updating analyses suggesting a much higher fatality rate, a high reproduction rate, evidence of airborne spread, asymptomatic transmission, and long-COVID symptoms. Indeed, a later survey by Southwell et al 2020 showed: “Past influenza vaccination behavior predicted willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine in the future among Americans.” That is, despite newer information about the severity of COVID-19, respondents continued to anchor their decisions to the flu.

Now imagine that instead of the flu, early reports compared COVID-19 to a more fear-inducing disease: It is a virus-borne respiratory illness, featuring Ebola-like symptoms such as fever, sore throat, aches, and fatigue. It is far deadlier than Ebola, with a similar reproduction rate. Unlike Ebola however, which is mostly transmitted through direct contact, COVID-19 is a respiratory disease that can also be transmitted through respiratory droplets, and is potentially airborne. A little more terrifying now? All of this information was available early on in the pandemic, and the disease could just as easily have been compared to Ebola as it was to the flu. Do you think this might have affected social distancing, masking, or vaccine uptake?

Anchors aweigh!

The order in which information is presented is important because the human brain naturally favours earlier information over evidence provided later. This phenomenon is called the anchoring effect :

“The anchoring effect is a cognitive bias that describes the common human tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered”

It’s not that people don’t adjust their initial impressions at all, but rather that they under-adjust given new information – this is why the bias is sometimes referred to as the anchor-and-adjust heuristic.

One of the most common ways to study this is to tell people how difficult a task is before asking them how well they think they’ll do. Given the same task, people primed to think it will be hard (a low anchor) will rate themselves as less able and then will give up quicker than those who were primed to think it would be easy (a high anchor).

In other words, higher anchors lead to higher estimates of self-efficacy, and increased persistence behaviour in the task (Cervone & Peake, 1986; Peake & Cervone, 1989; Lee Ang & Ming Lim, 2007). Take this with a grain of salt, though, because other studies (Switzer & Sniezek, 1991; Jung, Perfecto, & Nelson, 2016) suggest that the anchoring effect may not always translate to actual behaviour in real-world situations.

There has also been lots of research in the economic sphere. The anchoring effect is responsible for your brain thinking something that’s on sale for $80 down from $100 is better than the same item just listed for $80 originally.

In one famous experiment, students were asked to write down the last two digits of their social security number and then rate how much they would pay for certain items. Those with higher numbers said they would pay more than those with lower social security numbers.

Anchoring in the pandemic

A notorious example in the pandemic is the arguments about the efficacy of mask-wearing. Masks were initially reported as insignificant in Western media in February, 2020. This view changed a few months later, in April, 2020, when they were considered effective. Now, with the Omicron variant circulating, they’re considered even more important.

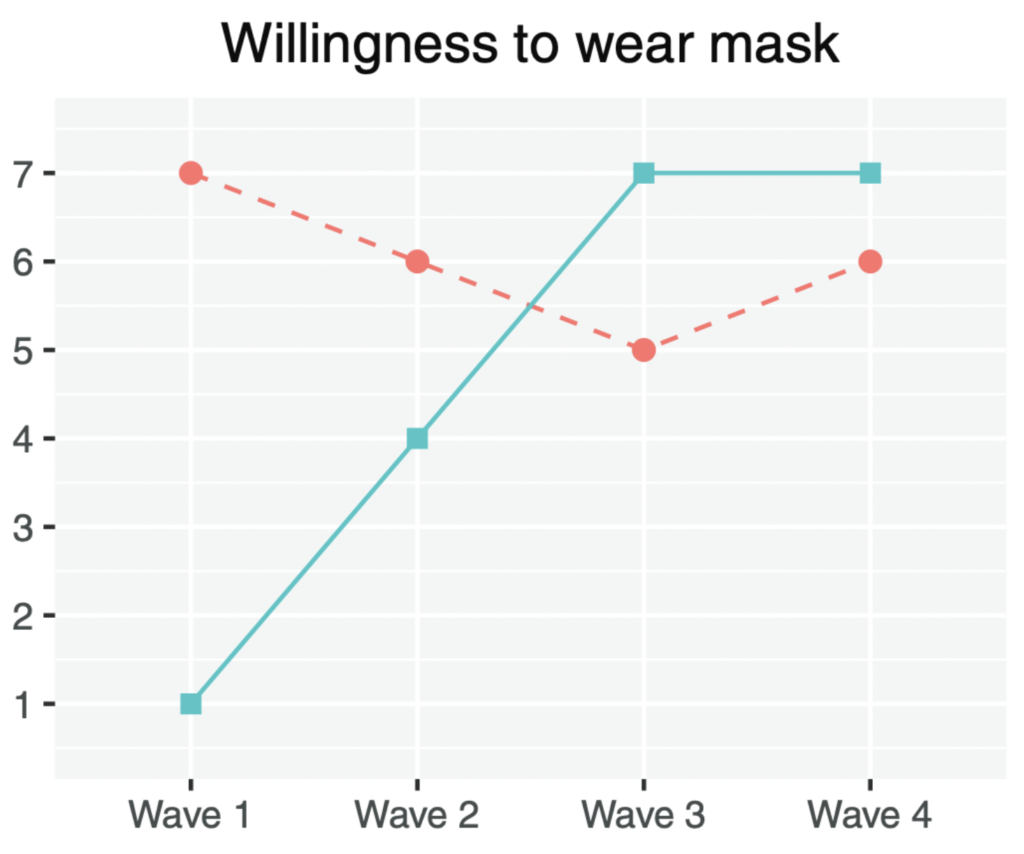

However, public views were slow to adjust from initial impressions (image from Li et al, 2022). The graph below shows the willingness to wear a mask in the USA (blue) and in China (red). In the USA, where mask-wearing was not the norm before, it took almost 6 months for public perception to catch up to the science.

The study authors speculate:

“… prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Americans had very low expectations that wearing masks would protect against seasonal influenza. This low perceived efficacy may be one key reason for the slow adoption of mask wearing by our U.S. participants early in the pandemic. However, as scientific evidence accumulated and authorities began to clearly endorse mask wearing, most U.S. participants became more willing to wear masks in public space.”

The good news from this study is that views do adjust, eventually. In general, the science and public health communications experts suggest leveraging trust, expert opinion, consistent messaging, and audience-specific messages, as best practices in science communication.

Written by Anthony Morgan

Edited by Jon Farrow

Share our original Tweet!

Thought experiment:

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) May 18, 2022

What if, in January 2020, headlines read:

“There’s a new virus with symptoms like Ebola: Fever, sore throat, aches, and fatigue.” #ScienceUpFirst

[1/7] pic.twitter.com/lb9T0mIZlh

View our original Instagram Post!