Increased polarization of citizenry is observed in seventeen European and North American countries, whereby centrist positions are shifting towards extremes on either side of the political spectrum. This is most pronounced in the United States. (February 21, 2024)

Category: Misinformation 101

-

The dose makes the poison

The world isn’t fully black or white – and substances aren’t fully toxic or safe (1). Even water could be lethal if you ingest too much, too quickly. It is the dose that makes the poison – or the medicine – not the chemical itself (1,2,3).

To determine the toxicity of a substance, scientists will measure the effect of different doses on an organism – usually mice or rats. The dose at which half (50%) the test subjects die is used to estimate the human lethal dose 50 or LD50, which is usually expressed in mg of the substance per kg of body weight (mg/kg). The smaller the LD50 is, the more toxic the chemical is. In most cases, harmful effects will appear before the LD50 is reached. Plus, the LD50 can vary depending on how long the exposure to the chemical is or if it’s taken by mouth, applied to the skin, or injected into the blood (1,2,4,5,6).

But a substance can also be beneficial when administered in the correct dose. For example, acetaminophen, a common medicine used to reduce pain and fever, has a therapeutic effect when used at a dosage of 325 to 1,000 mg per dose, for a maximum of 4,000 mg per day. However, consuming more than the recommended dose can lead to liver damage or even death. This shows how the same substance can be a life-saving medication within a specific dosage range but a harmful poison outside of it (7,8,9,10).

Similarly, it is not because something is classified as carcinogenic that being exposed to it will automatically cause cancer (11). The dose, how you are exposed to it, and for how long are all key (4).

Want to learn more about how doses affect toxicity and safety? Engage with us and let’s explore together!

Sources: https://tinyurl.com/SUFDoseMakePoison

*Numbers presented in the figure are calculated based on LD50 for an average adult of 75 kg, 45 ml shooter with 40% alcohol, 240 ml cup of coffee, glass of 8 oz (1 cup) of orange juice, and 100g extra dark chocolate bars (70-85% cacao) (1,2,12,13).

Share our original Tweet!

View our original Instagram Post!

-

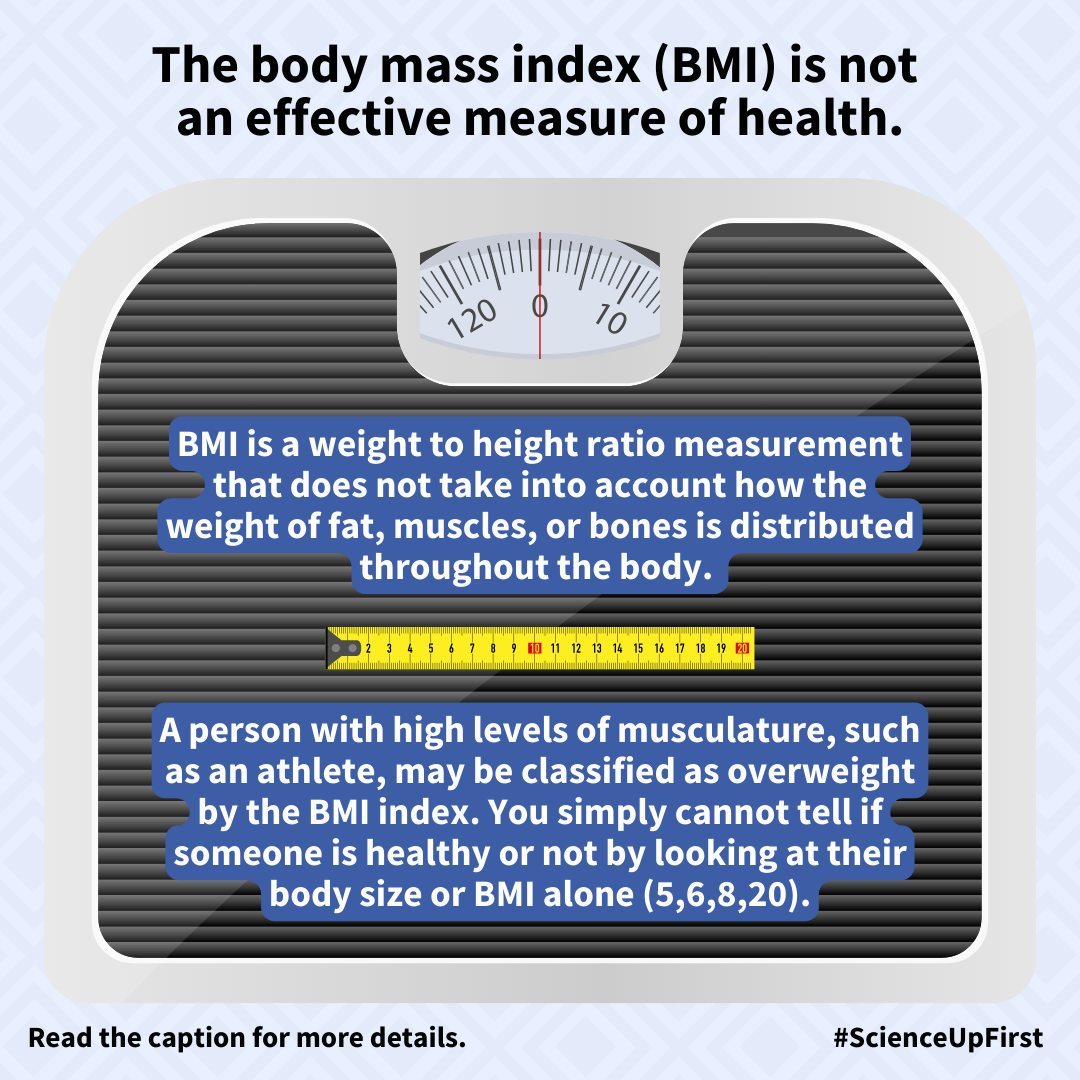

The body mass index (BMI) is not an effective measure of health.

With the 2024 Olympics having just wrapped up, we’ve been hearing lots of opinions on what an athletic body should look like. There’s no single answer – and no, someone’s BMI does not indicate how healthy or athletic they are.

Sources: https://tinyurl.com/SUFWeightStigma

Share our original Tweet!

View our original Instagram Post!

-

Misinformer Tactic: Stirring Up Emotions

Did you know that misinformation on the internet and social media often plays on your emotions to go viral? In particular, anger is frequently used to spread misinformation (1-3) .

Research shows that:- Tweets that provoke anger rather than joy tend to be retweeted more (3).

- Being angry also makes it easier to believe misinformation (4).

- People who are angry are more inclined to consider false information as “scientifically credible” (5).

View our original Instagram Post!Did you know that misinformation on the internet and social media often plays on your emotions to go viral?

Emotions can hinder our critical thinking. Read more on that and how to protect yourself here https://t.co/gumtyFpleV#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/wJbyqN9cOv — ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced’Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) July 8, 2024 -

If sharing a post had a loading screen

Ever notice how those loading screens in video games sneak in a few seconds of wisdom? They’re not just making you wait; they’re giving you pro tips to up your game!

What if your brain did the same for you when navigating the internet and social media?

Keep these tips in mind. Here are a few others as a reward for starting the side quest of reading the caption:

- Does the person making the claim have the relevant expertise?

- What is the position of most relevant experts on this topic?

- If there is a source for the claim, does the source actually say the same thing as what is claimed?

- Where is the source located on the hierarchy of evidence?

Let us know some questions you ask yourself when navigating potentially suspicious information online.

Share our original Tweet!

What if sharing a post had a loading screen, with a few quick tips on how to avoid regretful retweets? 🧠🔄

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) June 19, 2024

While the loading screen might not exist, you can still load your brain up with these great strategies!https://t.co/mjMr6kiokk#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/hdV4rxEzRyView our original Instagram Post!

-

Why do our brains love anecdotes?

We all love a good story, right?

Anecdotes can help convey information in a way that is easy to understand and remember (4,5). But sometimes our brains can latch onto these easy and emotional stories at the cost of considering more robust evidence (1,3,5). This can lead to some pretty harmful decisions (3)!

Read on to learn why we like anecdotes so much, and why this might be a problem. And if you find yourself being more convinced by a story than a statistic, take a step back and consider all the evidence before making your choice!

Sources: https://tinyurl.com/SUFAnecdotalEvidence

Share our original Tweet!

We all love a good story, right? 📖

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) June 13, 2024

But if you find yourself being more convinced by an anecdote than a statistic, take a step back and consider all the evidence before making your choice!https://t.co/XiIvMg0BhK#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/regHbP8vYGView our original Instagram Post!

-

Misinformer Tactic: Cherry Picking

Have you ever heard, “Meteorologists can’t predict the weather. Last week they said it was going to rain and it didn’t!”?

While it’s true that meteorologists sometimes miss the mark, a 5-day forecast can accurately predict the weather 90 percent of the time (1,2,3). Focusing only on those few misses while ignoring all the accurate predictions is an example of cherry-picking evidence.

Same goes with science. When scientists reach a consensus, it means that a vast majority of experts in a certain field agree based on extensive evidence (4). For example, over 97% of climate scientists agree that climate change is real and driven by human activities (5,6,7,8). It does not mean that there are no contradictory studies – there usually are (9). But picking only the studies that support your view while ignoring the bulk of evidence is misleading.

Cherry-picking happens when people intentionally or unintentionally select evidence that fits their narrative while ignoring all the data that might contradict it. This misinformer tactic is often used by denialists or people who support a controversial opinion (9,10). By only presenting the few examples or studies that best align with their view they make it seem like their idea actually aligns with the scientific consensus (10). Others will deny or discredit all work that goes against their belief, but accept the same scientific process when the findings align with their ideology (11).

As humans, we often select information that already aligns with our beliefs. That’s called a confirmation bias (10,11,12). To avoid doing unintentional cherry-picking, be mindful of your own bias, take time to form an opinion, and ask yourself if any other evidence might be available (10).

We are all a little biased. It’s human nature. But by recognizing our bias, we can avoid the cherry-picking trap! Let us know if you want to see more posts about human biases!

Sources: https://tinyurl.com/SUFCherryPicking

Share our original Tweet!

Have you ever heard of “cherry-picking”?

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) May 31, 2024

This is when certain data has been selected to fit a specific narrative. It’s a misinformer tactic often used by people with controversial opinions…

Learn more here 👇 https://t.co/YjMBJ4qIfR#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/xzM9VJocHAView our original Instagram Post!

-

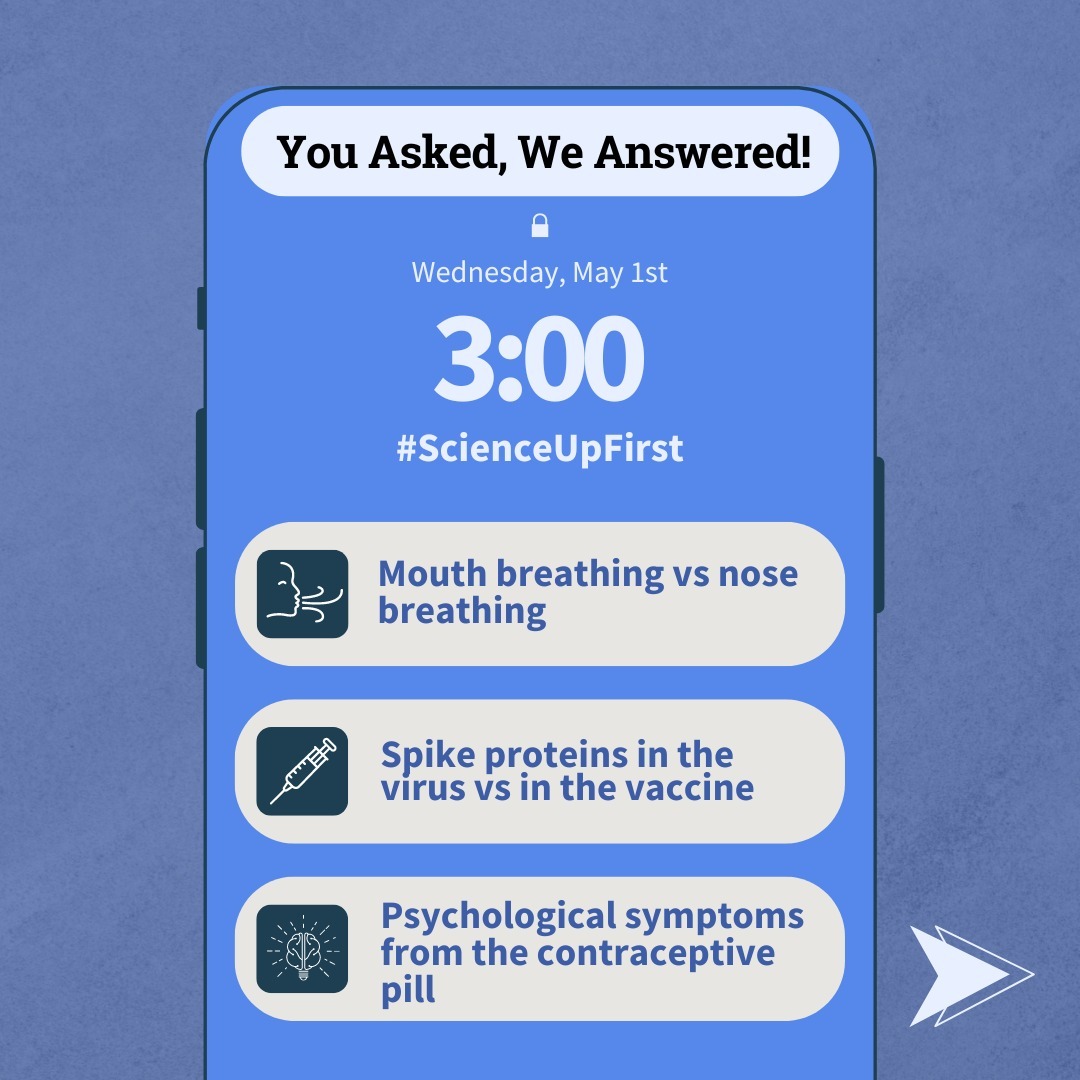

You asked, we answered: April 2024

We love reading your questions and always encourage curiosity and digging deeper!

When you ask us questions we take the time to do some research and consult an expert on the matter when needed!

On the topic of mouth breathing vs nose breathing, there are many claims out there and it is a nuanced topic that may require its own post in the future. Don’t hesitate if you have questions. As a precaution and regardless of the claims made, any changes to your breathing habits should be done slowly and incrementally.

We also got an unusual question outside of our usual expertise but it made us laugh and learn something new, so we include it here as a bonus question:

“Is a shark’s brain actually the same shape as a uterus?”

Yes, they tend to be long and thin and can look like a spark plug or even a uterus sometimes because of the olfactory bulbs that can extend outwards (17,18)!

Sources: https://tinyurl.com/SUFApril2024

Share our original Tweet!

We love reading your questions and always encourage curiosity and digging deeper!

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) May 3, 2024

When you ask questions we take the time to do some research and consult an expert when needed!

Check out some of the questions that caught our attention https://t.co/Eam1rxGuIQ#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/eI0udeHjhzView our original Instagram Post!

-

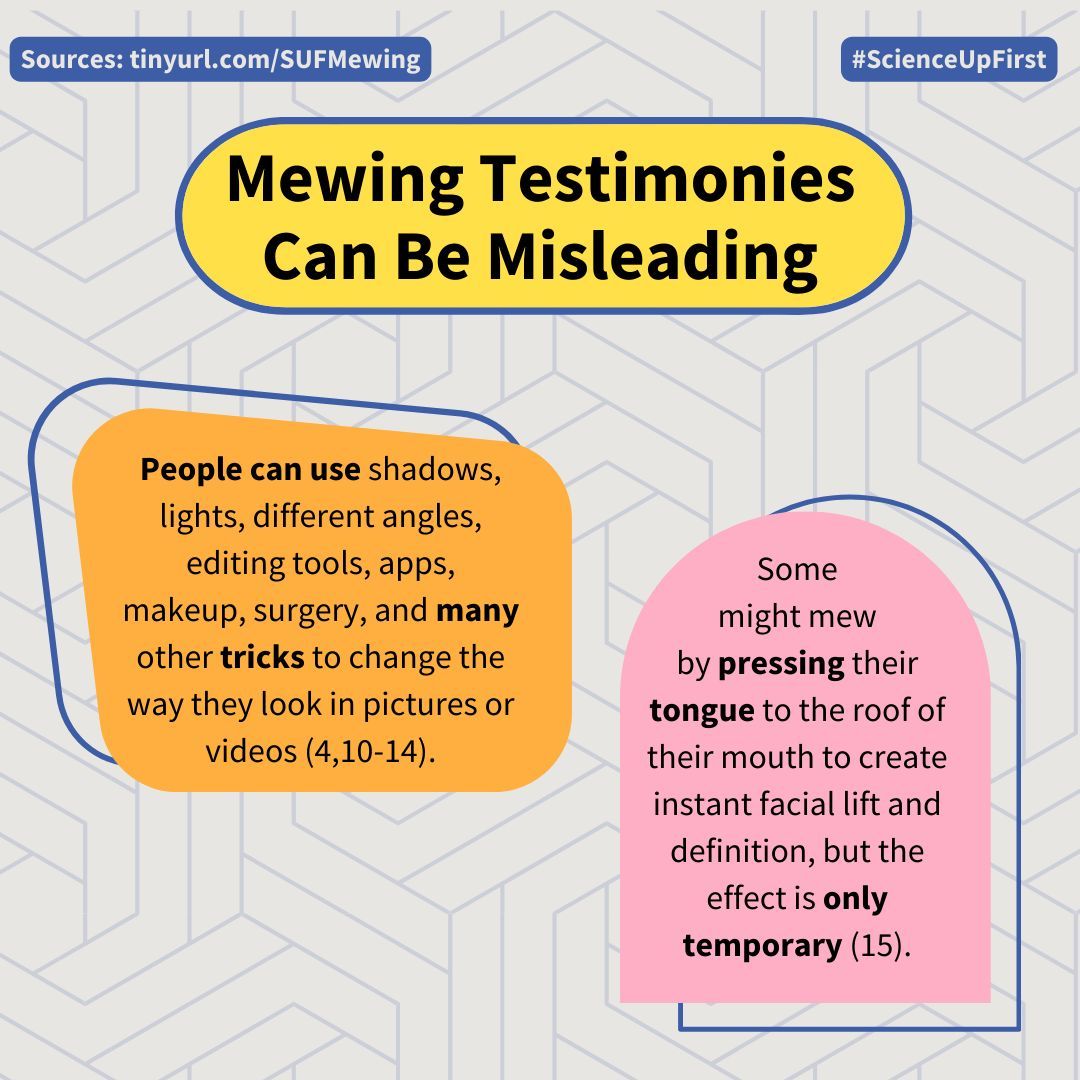

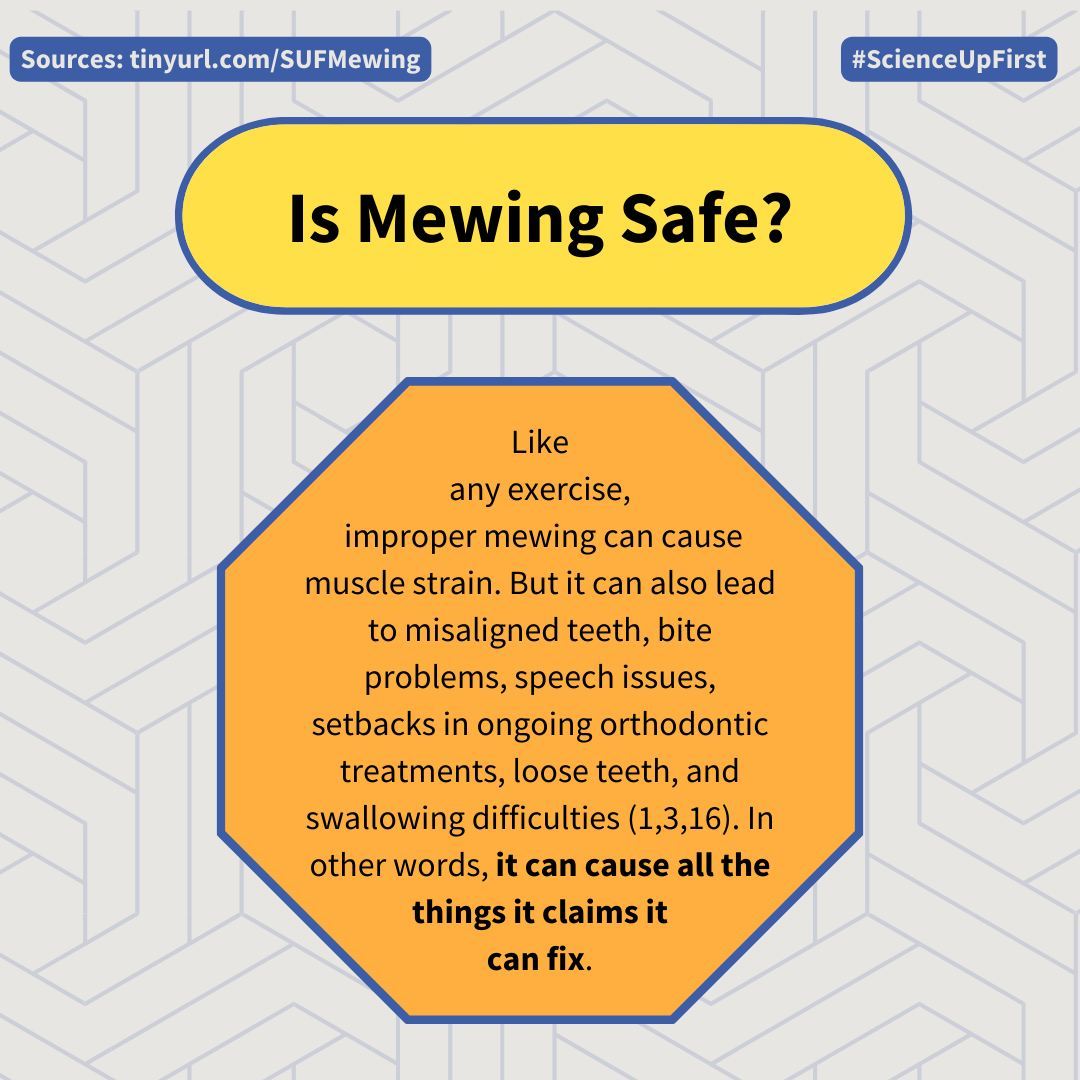

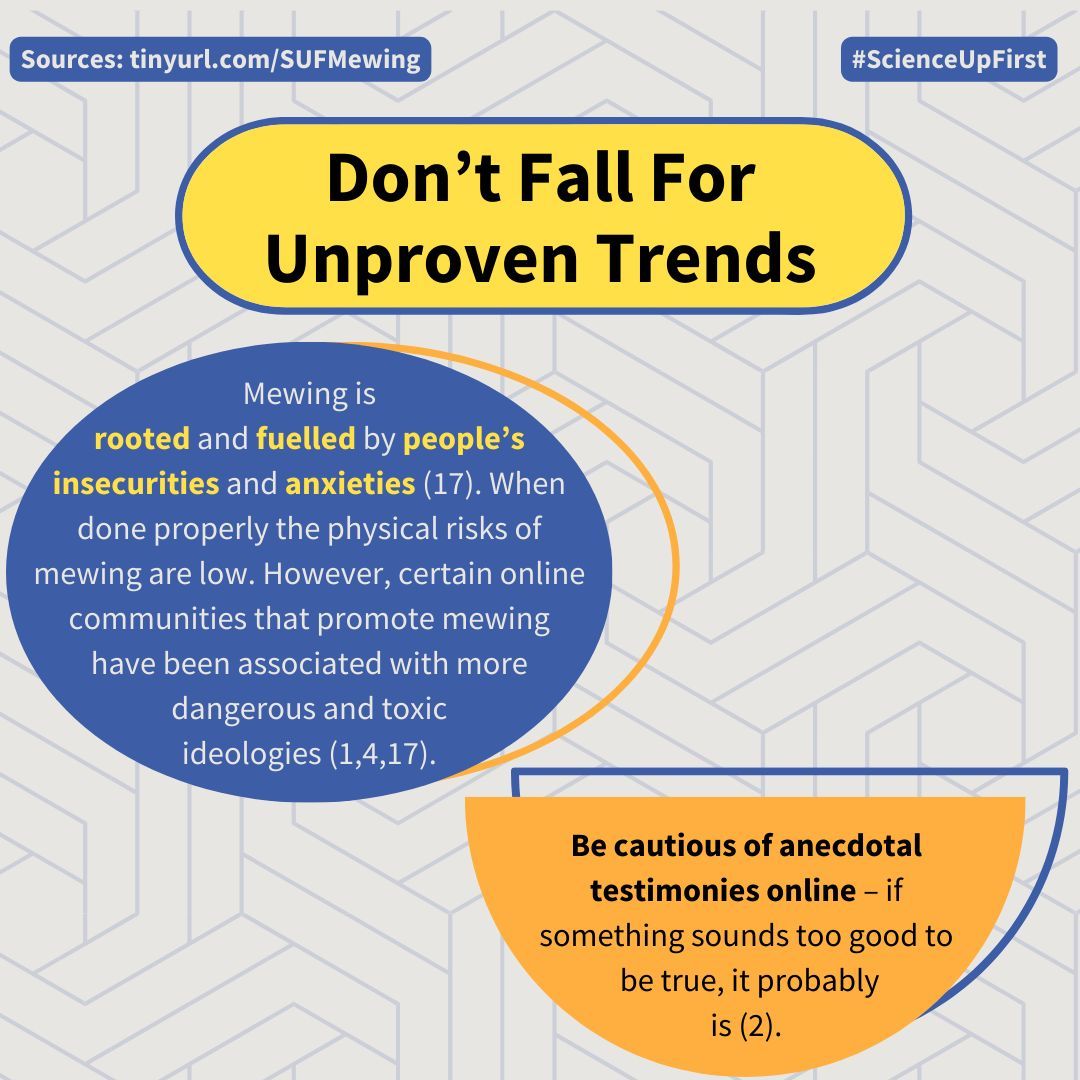

Did TikTok tell you about Mewing?

Have you ever heard of mewing, a practice that strengthens your jaw and improves the appearance of your face?

It recently became very popular on social media, but that doesn’t mean it works!

Let’s find out!

Sources: https://tinyurl.com/SUFMewing

Share our original Tweet!

Have you ever heard of mewing, a practice that strengthens your jaw and improves the appearance of your face?

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) April 18, 2024

It recently became very popular on social media, but that doesn’t mean it works!

Read more about it here https://t.co/UZrmdUbZfx#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/Oq9O0wlv9aView our original Instagram Post!

-

Why the internet went wild over HRH Princess Catherine’s “disappearance”

After the internet went wild with conspiracy theories about Her Royal Highness Princess Catherine (aka Kate Middleton), the Princess of Wales, stepping back from her public duties for a few months, the Royal Family has now released a statement about her health.

This was none of our business. So why was the internet so obsessed with #KateGate ?

Swipe through for just some of the key reasons why Princess Catherine’s absence captivated our conspiratorial minds.

Sources: https://tinyurl.com/SUFPrincessKate

Share our original Tweet!

The Royal Family has now released a statement about Princess Catherine's health after weeks of wild conspiracy theories.

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) March 27, 2024

This was none of our business. So why was the internet so obsessed with #KateGate? https://t.co/zeEbPK6hm1#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/ulV8rRWcRvView our original Instagram Post!

-

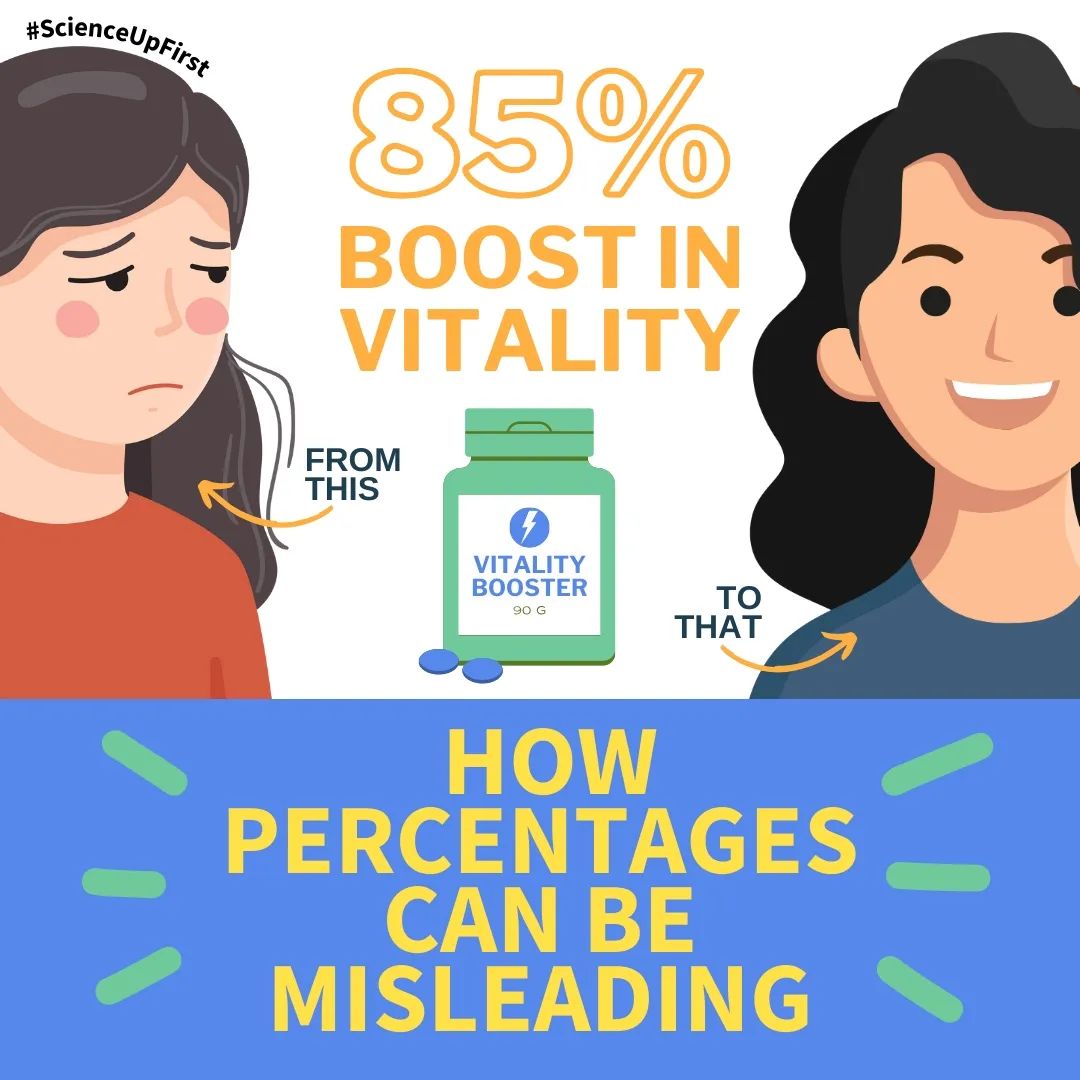

How percentages can be misleading

Have you ever noticed the use of percentages in health product advertisements? They’re useful tools for expressing the change between two numbers, but without context, they’re meaningless and can be misleading.

Make sure you see the big picture!

Thank you to @figures.first for this great collaborative post!

Sources: https://tinyurl.com/SUFMisleadingPercentage

Share our original Tweet!

Have you ever noticed the use of percentages in health product advertisements? Without context, they're meaningless and can be misleading.

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) March 20, 2024

Make sure you see the big picture!

Learn more here: https://t.co/lPHoSrvmIp#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/LmWetEDE4YView our original Instagram Post!

-

Be mindful of the Persecuted Hero Narrative

Be mindful of the Persecuted Hero Narrative.

This tactic aims to make the ‘hero’ appear more trustworthy than institutional authorities and mainstream media. This narrative works like this (1,2):

- Claims the world is controlled by biased and corrupt elites.

- “Exposes” said corruption by cherry-picking information and using anecdotal evidence to seem more relatable.

- Presents themselves as the hero who bravely reveals hidden truths, implying that those who trust institutional authorities are merely “sheep” following blindly.

- Claims they are being censored and persecuted for telling you the truth.

- Rallies followers in the name of freedom and justice.

By posing as the censored hero that is risking it all in the name of the truth, justice and freedom, they create a common enemy (e.g. mainstream media), and build a community of followers ready to defend the same goal (1,3). They also profit from spreading misinformation (2,4).

Sources: https://tinyurl.com/SUFPersecutedHero

View our original Tweet!

The persecuted hero tactic aims to make the "hero" appear more trustworthy than the authorities and mainstream media.

Learn more about this tactic here. https://t.co/W36rV9XpMq#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/60kb7uwQNF

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) March 1, 2024

View our original Instagram Post!

-

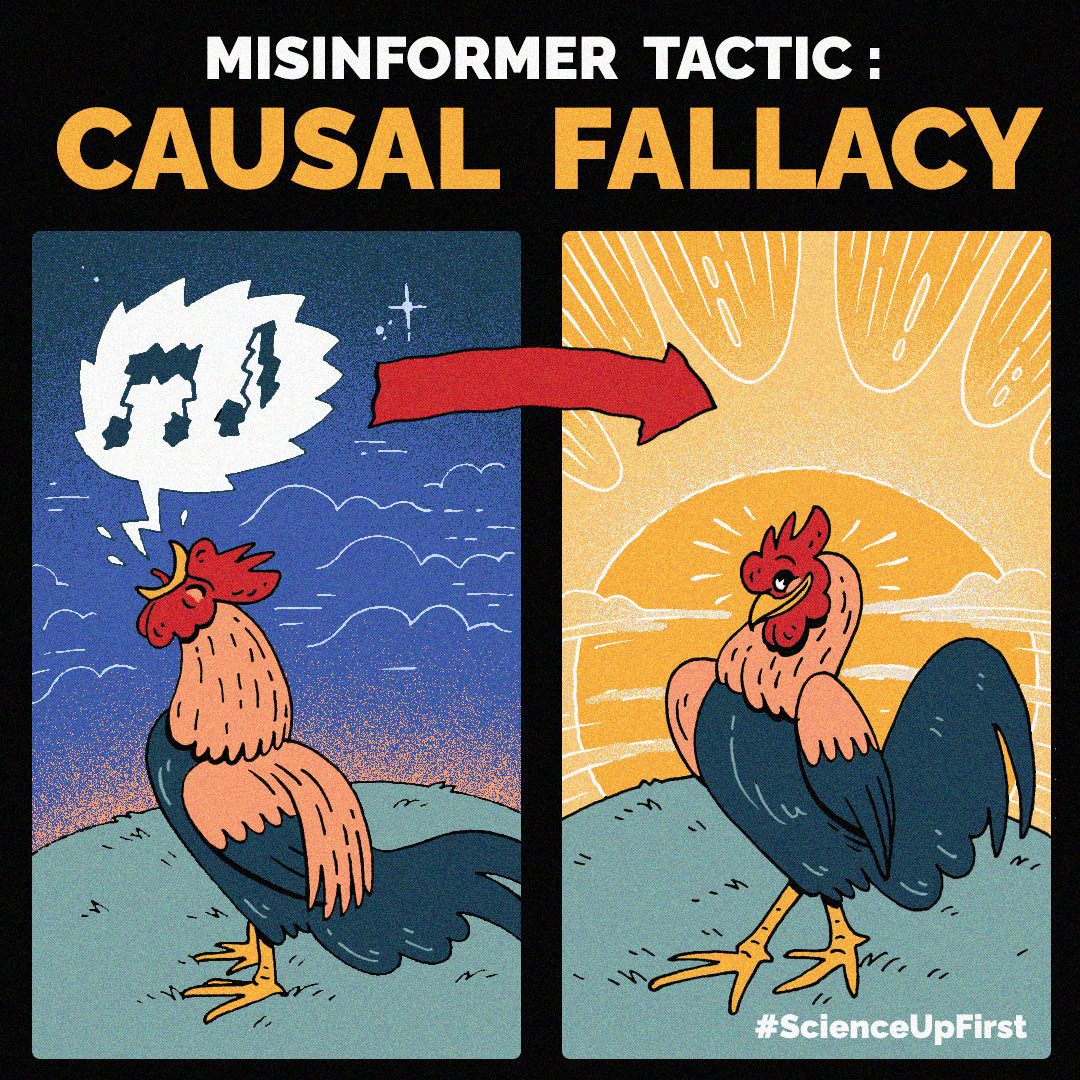

Misinformer Tactic: Causal Fallacy

Correlation does not equal causation!

The causal fallacy is a tactic that can trip up the best of us! Why? Our brains like to take shortcuts wherever possible. So when we see…

A followed by B .

Our brains want to jump to: A caused B.

While causation and correlation can exist at the same time, the two events are often unrelated. Even if the rooster does not crow, the sun will still come up.

Here is a COVID-19 example of the causal fallacy.

Misinformer: “My cousin got the vaccine and one month later had a heart attack. The shot caused him to have a heart attack!”

Reality: The COVID-19 vaccine is not a known cause of heart attacks. Every hour approximately 12 Canadian adults diagnosed with heart disease die. With 76% of Canadians fully vaccinated, the chances of having heart disease and being vaccinated are high. The two might correlate, but vaccination is not the cause.

Thanks to Jordan Collver for collaborating with us on this post. Jordan is an illustrator and science communicator specializing in using the visual and narrative power of comics to explore themes of science, nature, and belief.

We’re working on a series of misinformer tactics with Jordan so stay tuned for more.

Check out his work on his website and on Twitter.

Share our original Tweet!

Correlation does not equal causation! 📣📣📣

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) January 11, 2022

The causal fallacy is an easy trap to fall into 🕳

Why? Our brains like to take shortcuts wherever possible

🧵[1/4]#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/Px4pvMGc6fView our original Instagram Post!

-

Conspiracy Theory Crash Course

Have you ever been drawn into the realm of conspiracy theories? ️

These theories can be very compelling, and sometimes fun (ARE birds real?!), but conspiracy beliefs can also cause real harm.

Check out our crash course to learn more about what conspiracy theories are, why people believe them, and what we can do about them.

Share our original Tweet!

Have you ever been drawn into the realm of conspiracy theories? 👁️

— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced'Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) January 26, 2024

Check out our crash course to learn more about what these theories are, why people believe them, and what we can do about them.

The truth is out there! And it's also at https://t.co/56P9pHuHca#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/ima0uYQxGBView our original Instagram Post!

Sources- The Conspiracy Theory Handbook

- Shining a spotlight on the dangerous consequences of conspiracy theories

- Who Is Likely to Believe in Conspiracy Theories?

- Merchants of Doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming.

- From COVID-19 to alien contact, conspiracy theories are popular in Canada: survey

- Belief in conspiracy theories: Basic principles of an emerging research domain

- The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories

-

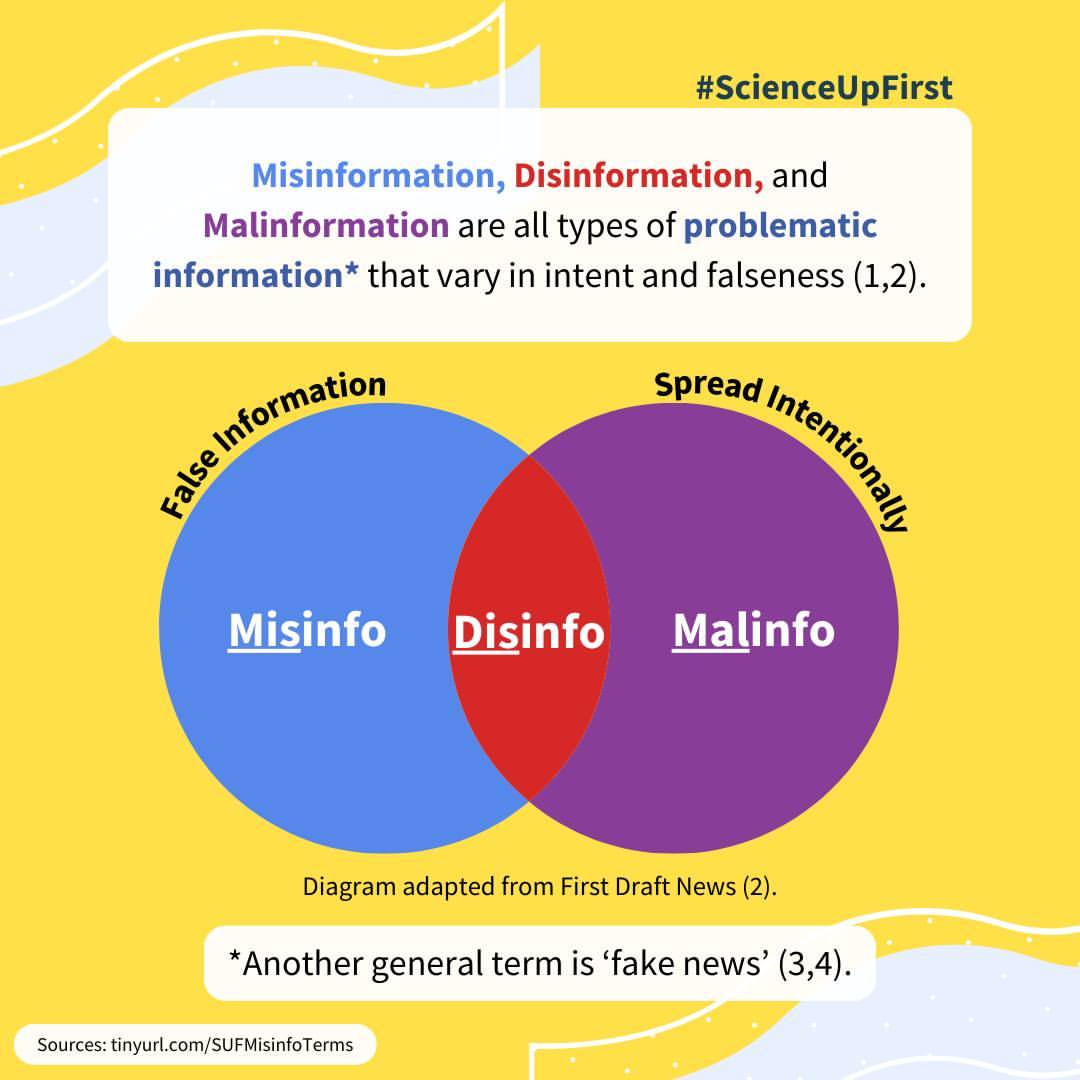

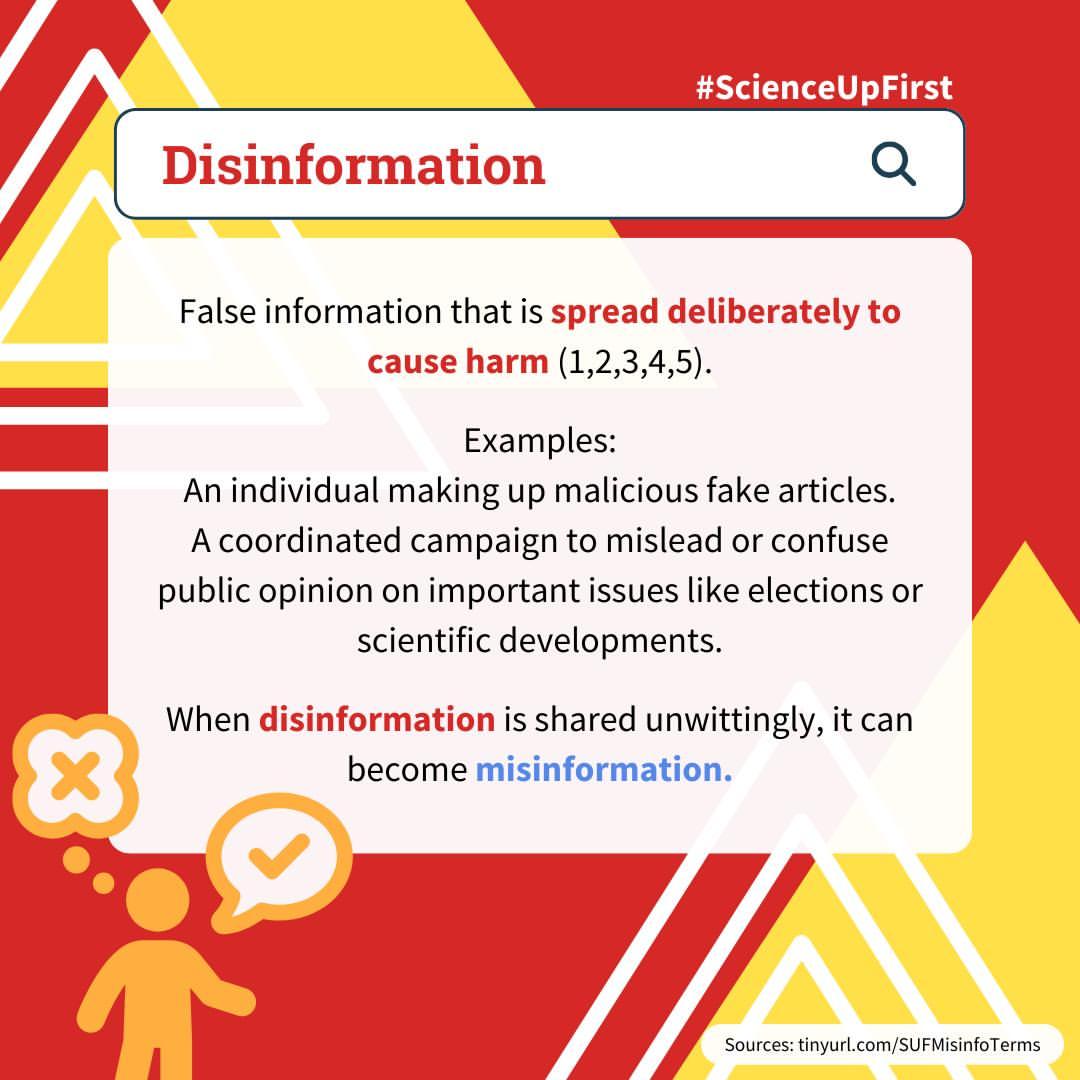

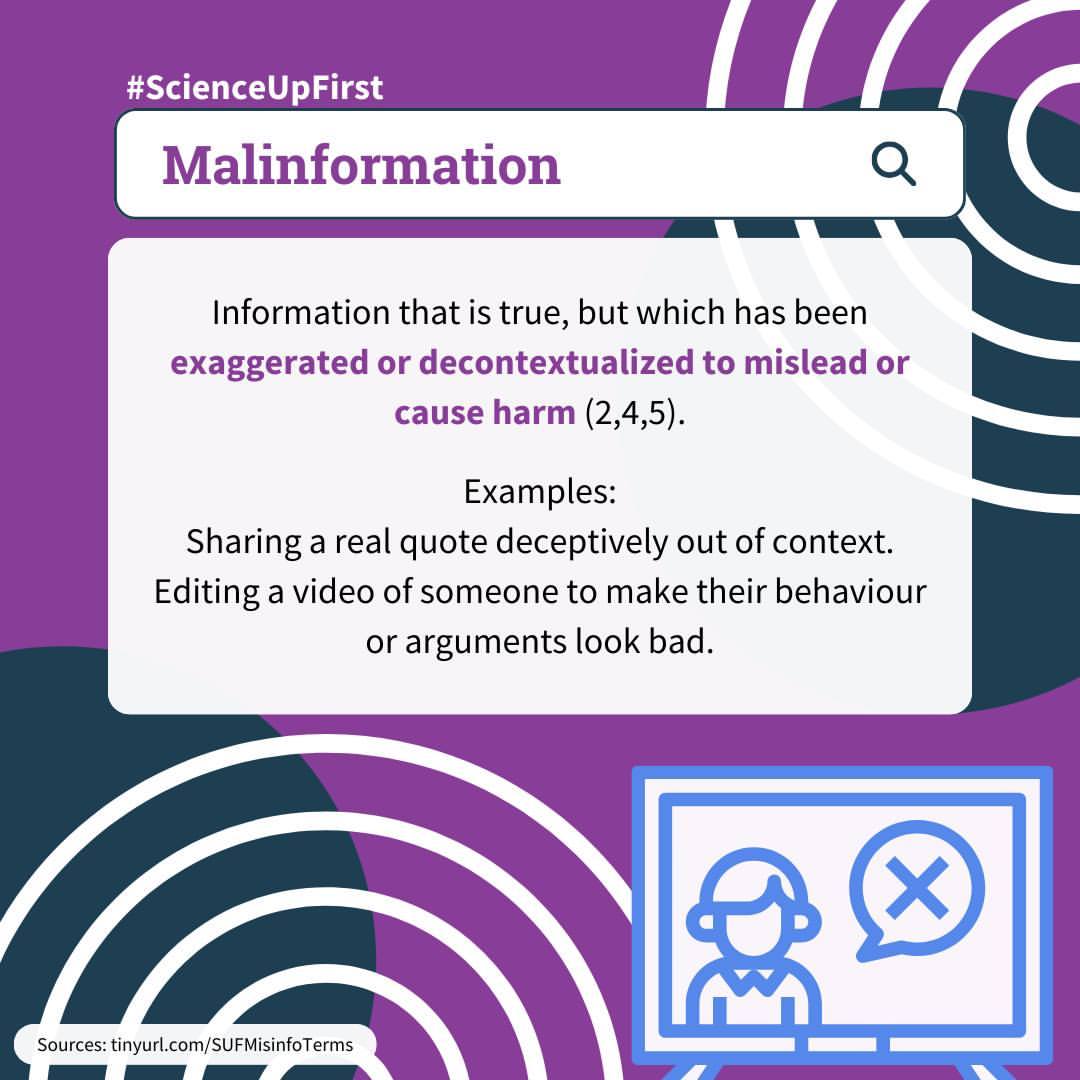

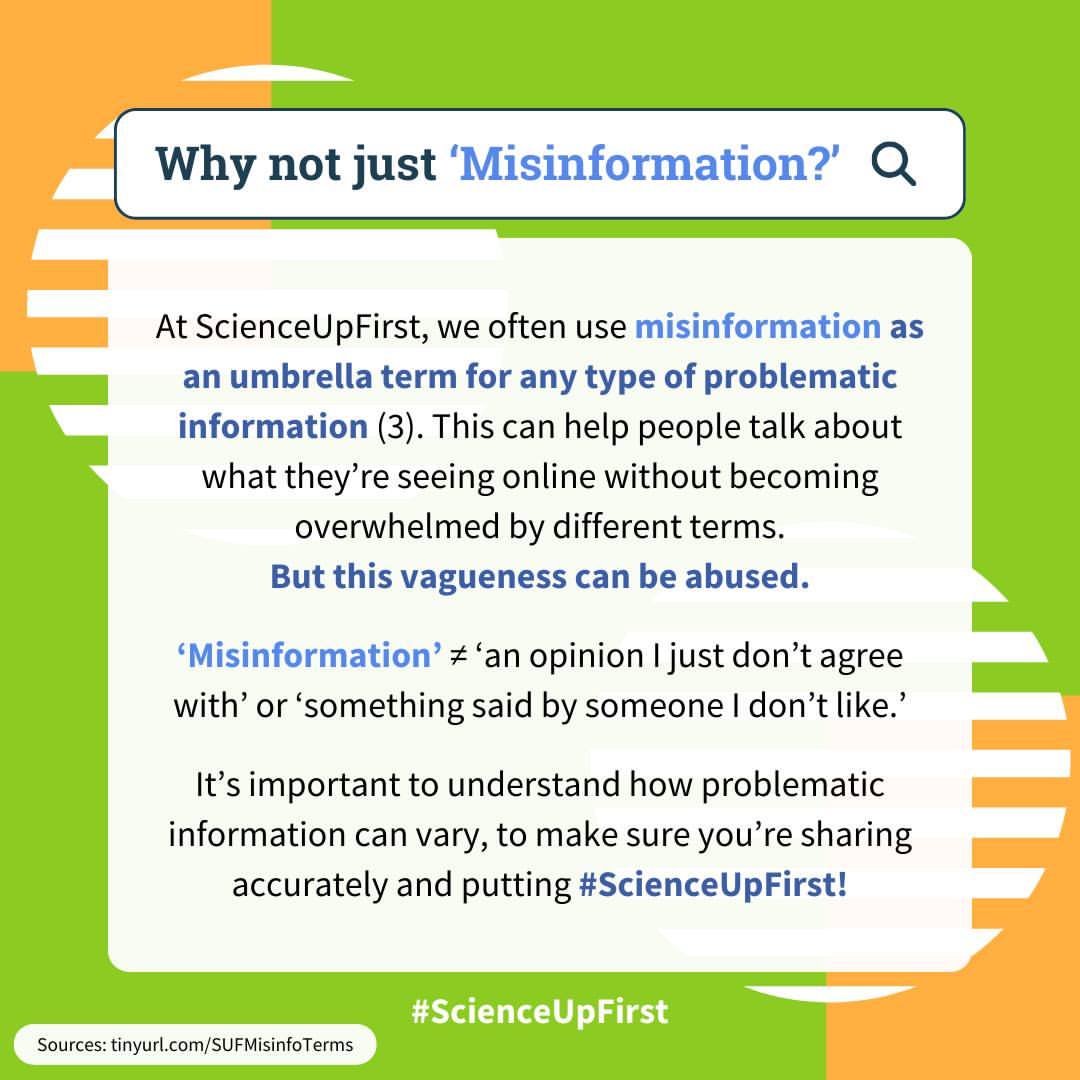

Let’s clear up some vocabulary

Can you tell different types of problematic information apart?

We often use ‘misinformation’ as an umbrella term for any false content online, but sometimes more specific language can help clear up confusion. So here’s your vocab lesson!

Misinformation: False information spread unintentionally.

Disinformation: False information spread intentionally.

Malinformation: True information spread intentionally in a way meant to cause harm.Share our original Tweet!

Misinformation can be a useful umbrella term, but sometimes more specific language is needed. Read more about

• Misinformation

• Disinformation

• Malinformation

And learn to spot the difference! 👇https://t.co/br1ZffLu54#ScienceUpFirst pic.twitter.com/6Y5QqsJQe1— ScienceUpFirst | LaScienced’Abord (@ScienceUpFirst) January 10, 2024

View our original Instagram Post!

Sources- Lexicon of Lies: Terms for Problematic Information

- Understanding Information disorder

- The world of misinformation and fake news is full of confusing vocabulary

- Journalism, fake news & disinformation: handbook for journalism education and training | FR : Journalisme, fake news & désinformation: manuel pour l’enseignement et la formation en matière de journalisme

- How to identify misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation | FR : Repérer les cas de mésinformation, désinformation et malinformation