New methods exist for identifying cancer misinformation online by building misinformation-detecting algorithms that can identify core linguistic characteristics. These characteristics can include for example, certain hashtags, expressions using absolutes, and specific URLS. Combined with manual labeling, these algorithms can help aid detection efforts.

Category: Misinformation 101

-

POV: Following an Influencer’s Morning Routine

Phew… that was just the first few minutes of an influencer’s day! 😮💨

Elaborate morning routines can look glamorous, but they’re often not backed by science! For a deeper dive on each step, check out our sources below.

Sources- Nocturnal mouth-taping and social media | Science Direct

- Dr. Nighat Arif on Mouth Taping | Instagram

- Breaking sociThe safety and efficacy of mouth taping in patients with mouth breathing, sleep disordered breathing, or obstructive sleep apnea | Plos One

- Cold plunging: does it live up to the hype?| ScienceUpFirst

- Did TikTok tell you about Mewing? | ScienceUpFirst

- Supplements & Vitamins can potentially make you sick | ScienceUpFirst

- Supplements and Vitamins: The Buzz Word Effect | ScienceUpFirst

- How much water do you need to drink daily? | ScienceUpFirst

- Should you use shampoo that is sulfate free? | ScienceUpFirst

- Should you buy aluminum-free deodorant? | ScienceUpFirst

Share our original Bluesky Post!

Phew… that was just the first few minutes of an influencer’s day! 😮💨 Elaborate morning routines can look glamorous, but they’re often not backed by science! For a deeper dive on each step, check out our sources: tinyurl.com/SUFInfluencerRoutine #ScienceUpFirst #TogetherAgainstMisinformation

— ScienceUpFirst (@scienceupfirst.bsky.social) June 26, 2025 at 4:19 PM

[image or embed]View our original Instagram Post!

-

Human Reviewers’ Ability to Differentiate Human-Authored or Artificial Intelligence–Generated Medical Manuscripts: A Randomized Survey Study

Medical manuscripts generated by AI are perceived by humans to be almost indistinguishable from human generated ones. There is heightened concern around the potential for fake research to be created and shared.

-

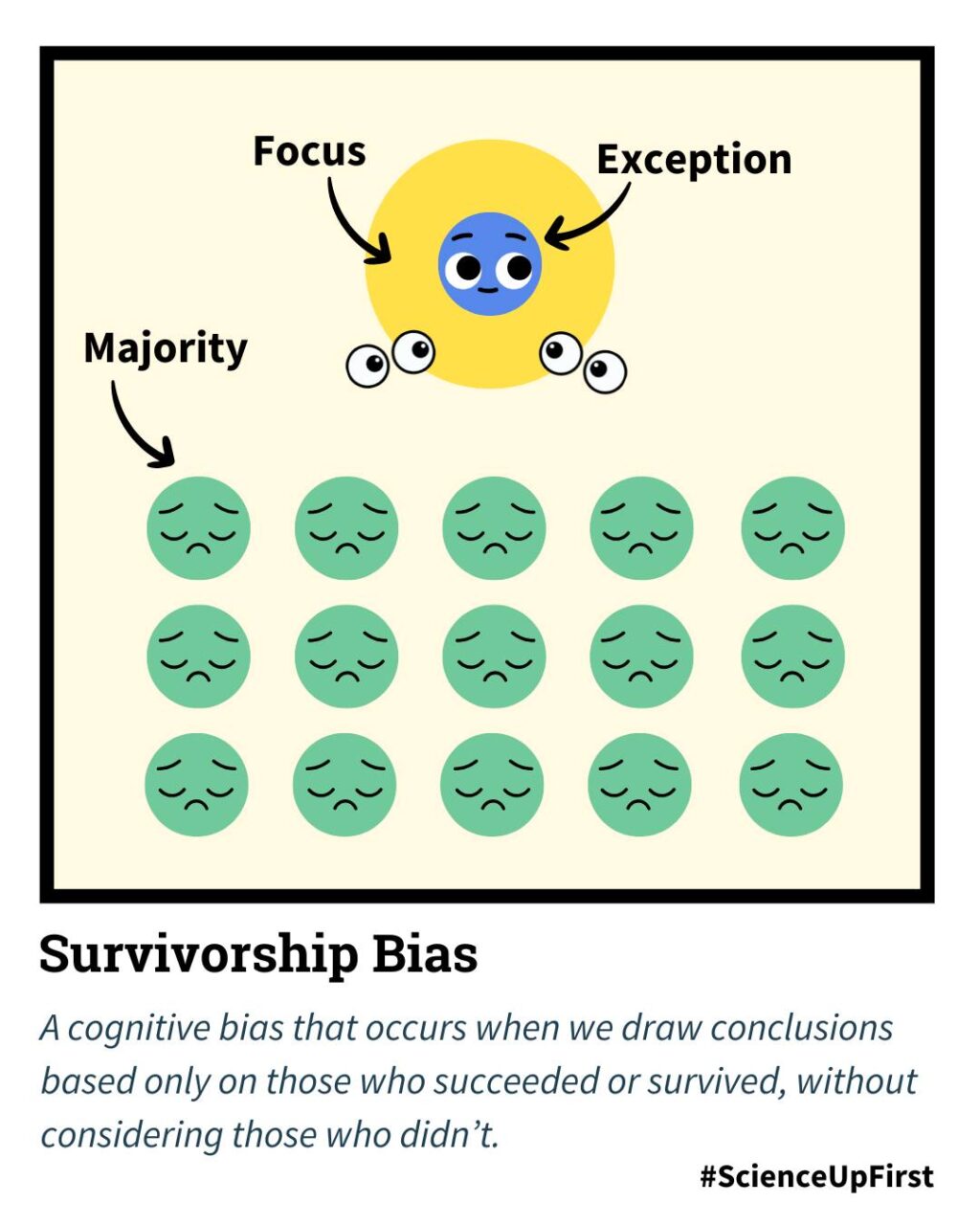

Survivorshop Bias

Survivorship bias is a cognitive bias that happens when we focus – sometimes unintentionally – only on the people or things that “made it through” a situation, and ignore those that didn’t. When that happens, we get a distorted picture of reality (1).

This bias shows up in many ways. Someone might say, “My great-uncle smoked his whole life and lived to 90, so smoking can’t be that bad.” But the people who smoked and died young aren’t here to tell their story – their stories are missing. The same thing happens when people say, “I didn’t get the vaccine and I was fine,” without considering the many who weren’t so lucky (1,2,3).

Survivorship bias can also affect research (1,3). For example, a study suggested that older adults who drank more wine lived longer than those who drank less or not at all – implying that drinking wine helps people live longer (4). But this can be misleading. Many people who were harmed by heavy drinking may have already died before the study started, so they weren’t counted. Others might have quit drinking because of health problems and ended up in the “non-drinker” group, making the drinkers look healthier by comparison (3,4,5).

Another great example comes from how the American military decided where to reinforce WWII airplanes. If they had only considered the bullet holes on the planes that returned, they would have missed a crucial piece of insight – those areas weren’t fatal. The real areas that needed reinforcement, were the places where bullets hit and caused planes not to return (6).

When we only look at people who completed a treatment or succeeded in a program, we miss those who dropped out or didn’t make it. That can lead us to believe something works better than it actually does (1,7,8,9).

This matters because it can lead us to make decisions based on incomplete data (1). Looking at both successes and setbacks helps us see the full picture – and make better choices.

Sources- Why do we misjudge groups by only looking at specific group members? | The Decision Lab | 2024

- Never take health tips from world’s oldest people, say scientists | The Guardian | 24 August 2024

- Nutrition and venous thrombosis: An exercise in thinking about survivor bias | Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis | January 2019

- Wine Consumption and 20-Year Mortality Among Late-Life Moderate Drinkers | Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs | January 2012

- Do “Moderate” Drinkers Have Reduced Mortality Risk? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Alcohol Consumption and All-Cause Mortality | Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs | 16 March 2016

- Survivorship Bias: The Mathematician Who Helped Win WWII | Cantor’s Paradise | 29 October 2020

- Uncovering survivorship bias in longitudinal mental health surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic | Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences | 26 May 2021

- The impact of survivorship bias in glioblastoma research | Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology | August 2023

- Survivor bias and risk assessment | European Respiratory Journal | 2012

Share our original Bluesky Post!

"I smoked all my life and I'm fine" doesn't erase the stories of those who are no longer here to testify. That's survivorship bias. It distorts our view of reality—and can lead to poor decisions. 👉https://scienceupfirst.com/misinformation-101/survivorshop-bias/ #ScienceUpFirst

— ScienceUpFirst (@scienceupfirst.bsky.social) June 19, 2025 at 12:19 PM

[image or embed]View our original Instagram Post!

-

Misinformation Research Matters!

Most Canadians and Americans are concerned about misinformation (1,2). But earlier this year, a U.S. Presidential Action ended National Science Foundation (NSF) support for misinformation research, claiming that it interferes with free speech (3-6).

This research is important, and restricting it can cause harm.

Individually, misinformation can cause loss of trust, confusion, stress, and lead to physical harm (7-17). For society, misinformation can create economic and political distress, prevent effective emergency responses after crises, threaten public health, and create or worsen violence and discrimination (7,8,12,15-25).

Misinformation has broad impact, and is studied by many disciplines including computer science, economics, politics, law, and social science (16,26). This research helps us understand how false information spreads, how it can harm us, and what we can do about it (16,26,27). Cuts to this research may mean fewer solutions to the problems created by misinformation.

The statements from the White House and the NSF claim that misinformation research hurts free speech (3,4). This is not true. Many evidence-based responses to misinformation involve empowering people to navigate the internet better without removing any posts (17,28,29). Moderating false information online – which is supported by most Americans, though support has declined slightly over the past few years – is only one tool in the toolbelt (30-32).

Sources- Concerns with misinformation online, 2023 | Statistics Canada | 20 December 2023

- The majority of Americans are concerned about misinformation in the news, according to new research | BBC Media | 29 October 2024

- RESTORING FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND ENDING FEDERAL CENSORSHIP | The White House | 20 January 2025

- Updates on NSF Priorities | U.S. National Science Foundation | 9 June 2025

- Trump Administration Cancels Scores of Grants to Study Online Misinformation | The New York Times | 15 May 2025

- Trump science cuts target bird feeder research, AI literacy work and more | AP News | 24 April 2025

- Infodemics and health misinformation: a systematic review of reviews | Bulletin of the World Health Organization | 30 June 2022

- The impact of fake news on social media and its influence on health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review | Zeitschrift fur Gesundheitswissenschaften [Journal of Public Health] | October 2021

- Fake News and Alternative Facts: Finding Accurate News: Why is Fake News Harmful? | ACC Library Services | 13 June 2025

- Nigeria records chloroquine poisoning after Trump endorses it for coronavirus treatment | CNN | 23 March 2020

- Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media: Systematic Review | Journal of Medical Internet Research | 20 January 2021

- The disaster of misinformation: a review of research in social media | International Journal of Data Science and Analytics | 15 February 2022

- Dealing with Propaganda, misinformation and fake news – intro | Council of Europe – Democratic Schools for All | 2019

- The Landscape of Disinformation on Health Crisis Communication During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ukraine: Hybrid Warfare Tactics, Fake Media News and Review of Evidence | JCOM – Journal of Science Communication | 8 September 2021

- The causes, impacts and countermeasures of COVID-19 “Infodemic”: A systematic review using narrative synthesis | Information Processing and Management | 4 August 2021

- (Why) Is Misinformation a Problem? | Perspectives on Psychological Science | 16 February 2023

- How to Address Misinformation—Without Censorship | TIME | 6 May 2025

- PROPAGANDA AND CONFLICT: EVIDENCE FROM THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE | The Quarterly Journal of Economics | November 2014

- Another Hurdle in Recovery From Helene: Misinformation Is Getting in the Way | The New York Times | 6 October 2024

- COVID-19: time to flatten the infodemic curve | Clinical and Experimental Medicine | 8 January 2021

- Facilitators and Barriers of COVID-19 Vaccine Promotion on Social Media in the United States: A Systematic Review | Healthcare | 8 February 2022

- What factors promote vaccine hesitancy or acceptance during pandemics? A systematic review and thematic analysis | Health Promotion International | 17 February 2022

- Misinformation of COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy | Nature | 11 August 2022

- Parental Perspectives on Immunizations: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Childhood Vaccine Hesitancy | Journal of Community Health | 23 July 2021

- COVID-19 pandemic fuels largest continued backslide in vaccinations in three decades | World Health Organization | 15 July 2022

- A survey of expert views on misinformation: Definitions, determinants, solutions, and future of the field | Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review | 27 July 2023

- Liars know they are lying: differentiating disinformation from disagreement | Humanities and Social Sciences Communications | 31 July 2024

- Evidence-based strategies to combat scientific misinformation | Nature Climate Change | 14 January 2019

- Countering Disinformation Effectively: An Evidence-Based Policy Guide | Carnegie Endowment for International Peace | 31 January 2024

- Across parties, Americans accept removal of false health info by social media companies, survey says | Boston University College of Communication | 25 January 2025

- Support dips for U.S. government, tech companies restricting false or violent online content | Pew Research Center | 14 April 2025

- Online content moderation: What works, and what people want | MIT Management Sloan School | 31 March 2025

Share our original Bluesky Post!

Research on misinformation is vital and recent funding cuts in the U.S. have put everyone at risk. Understanding misinformation = better protection against it. 👉 scienceupfirst.com/misinformati… #ScienceUpFirst

— ScienceUpFirst (@scienceupfirst.bsky.social) June 18, 2025 at 9:35 AM

[image or embed]View our original Instagram Post!

-

AI has a search citation problem

Analysis on different AI search engines (Chatbots) finds an inability for the AI programs to decline answering questions when they are unsure of accuracy, thus creating false or ambiguous content in response to prompts. Links and citations found in the AI’s answers often contain false, inaccurate, or faulty links and citations.

-

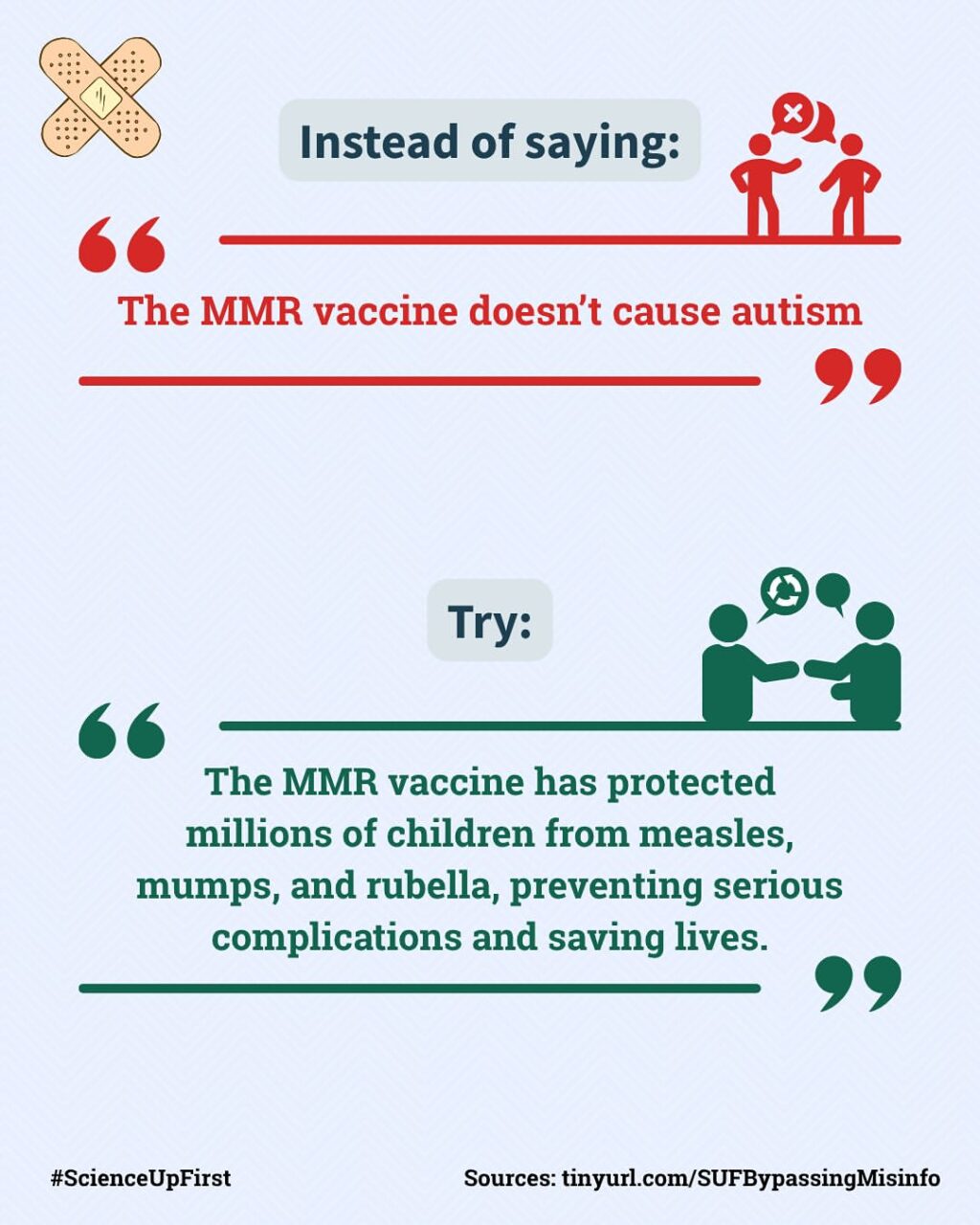

You don’t always have to debunk a false claim to make a difference.

When someone believes something that’s inaccurate, our first instinct is often to correct it with facts. But that doesn’t always work like we hope it would.

Most people don’t like to be contradicted – especially if they care deeply about the topic. Plus, it’s not always easy to find the right words in the moment. You might know something sounds off, but might not have the right facts or numbers to explain why. Even experts sometimes need time to fact-check and respond clearly (1,2,3).

That’s where bypassing can come in handy.

Instead of arguing about what’s false, bypassing shifts the focus from the false information toward a new, more positive alternative (1,2,4).

For example, instead of saying, “No, vaccines don’t cause X,” you might say: “Vaccines have saved millions of lives and reduced childhood mortality worldwide.” (5).

By bypassing misinformation, you avoid confrontation and shift the conversation toward something about the same topic that is both accurate and positive (2,3,4).

But, keep in mind that, bypassing doesn’t aim to correct specific misconceptions or deeply held beliefs. And in some cases – like public health emergencies – a direct correction might still be your best tool. So before jumping in, ask yourself: What’s my goal here? Is it to prove that “vaccines don’t cause harm”? Or to reinforce that “vaccines save lives”? While the first might call for a correction, the second might benefit from bypassing (2,4).

Bypassing (1,4):

• Avoids making people feel attacked.

• Redirects the conversation toward shared values or outcomes.

• Makes space for more than one idea to co-exist – you can hold concerns, while also recognizing the benefits of something.By bypassing misinformation you are not erasing a false belief, but you are helping build up an alternative one, and that shift in focus can make a big difference (1,2,4).

Sources- Bypassing Versus Correcting Misinformation: Efficacy and Fundamental Processes | Journal of Experimental Psychology: General | November 2024

- Instead of Refuting Misinformation Head-On, Try “Bypassing” It | Annenberg | April 2023

- Is ‘Bypassing’ a Better Way to Battle Misinformation? | Annenberg | November 2024

- Don’t waste time correcting misinformation. Instead, try the “bypassing technique” | Big Think | January 2025

- Global immunization efforts have saved at least 154 million lives over the past 50 years | World Health Organization | April 2024

Share our original Bluesky Post!

Instead of arguing about what's false, bypassing shifts the focus from the misinformation to a new, more positive alternative. Here are some examples and why bypassing can be useful 👉 scienceupfirst.com/misinformati… #ScienceUpFirst

— ScienceUpFirst (@scienceupfirst.bsky.social) May 30, 2025 at 3:50 PM

[image or embed]View our original Instagram Post!

-

SIFT: 90s Rap Edition

Do you know the difference between vertical and lateral reading? Fact-checkers use lateral reading because it is faster, more efficient, and less biased than vertical reading.

The SIFT method involves:

S, stopping

I, Investigating the source

F, Finding better coverage and

T, Tracing the information.We’ll summarize each point for you so you know how to SIFT.

Did you know about this fact-checking method? Let us know and don’t hesitate to share this video with your loved ones!

Initial beat produced by Shayzex Beats and remixed by us.

We also did a post on SIFT that gets a little deeper into the process.

Share our original Bluesky Post!

Fact-checkers use lateral reading because it is faster, more efficient, and less biased than vertical reading. It’s called the SIFT method. 👉 scienceupfirst.com/misinformati… Questions about the SIFT method? Ask us in the comments! #ScienceUpFirst

— ScienceUpFirst (@scienceupfirst.bsky.social) May 28, 2025 at 10:51 AMView our original Instagram Post!

-

“They need to speak a language everyone can understand”: Accessibility of COVID-19 vaccine information for Canadian adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

Survey research shows Canadians with intellectual and developmental disabilities can struggle finding and understanding information about vaccines. Struggles are also evident in accessing vaccines, such as booking appointments. Information overload and inconsistent messaging present significant issues. Efforts can be made to strengthen trust in sources, clarity of information, and community engagement (i.e. with highly accessible information).

-

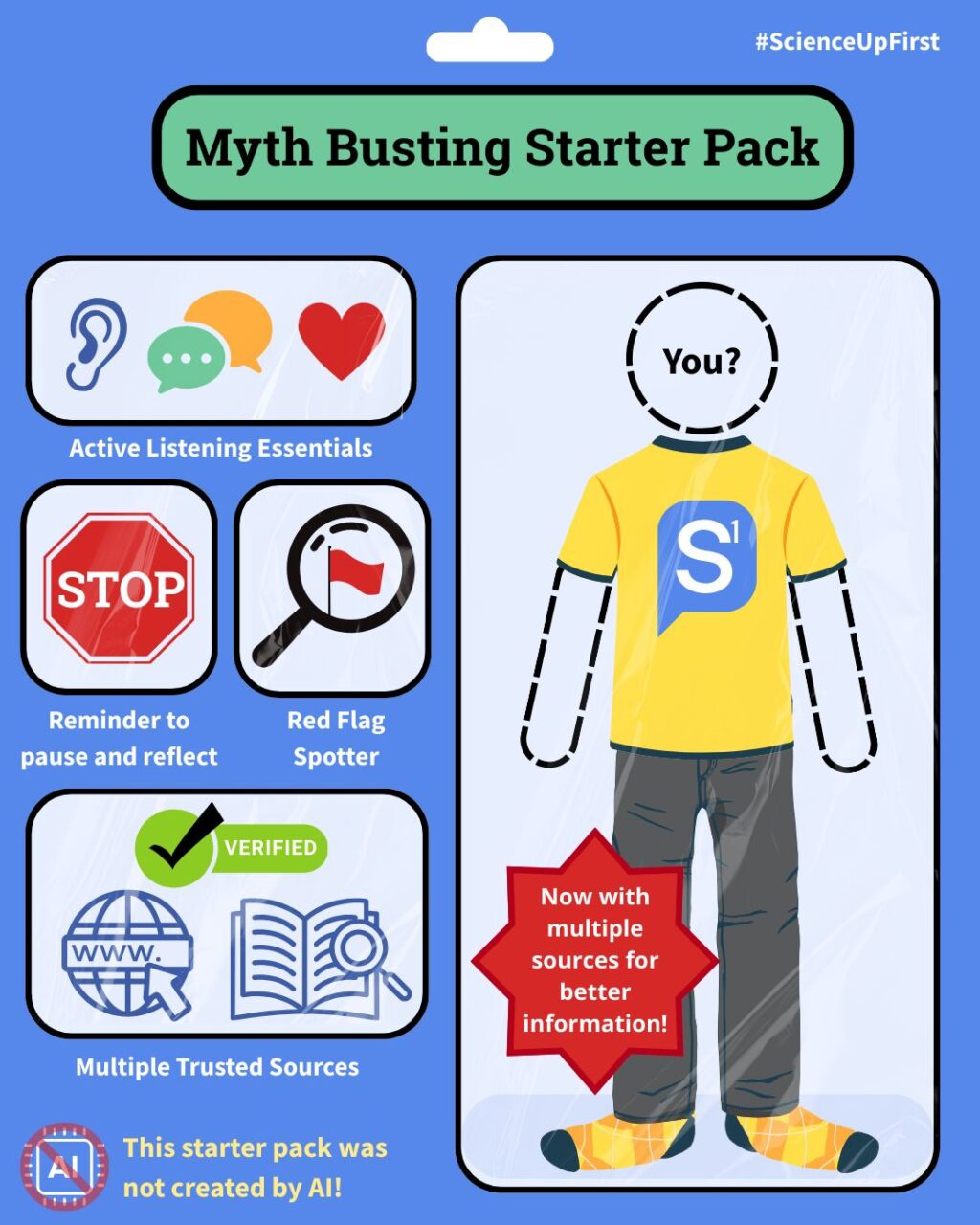

Myth Busting Starter Pack

We might be a little late to the trend, but this one was too good to pass up!

Introducing: ScienceUpFirst’s Myth Buster Starter Pack!

Here are four essential accessories for anyone aspiring to become a Myth Busting champion.

Listening & Empathy essentials: First, a great myth buster listens closely, opens respectful dialogue, and always approaches others with empathy — even when they don’t share their views. 💬🩵👂

A reminder to pause before sharing: A mindful myth buster also knows that one of the easiest ways to stop misinformation is to pause and ask: “Is this true?” before sharing information online. 🛑

Red flag spotter: Myth busters are also really good at spotting the various misinformers’ tactics and misleading reasoning that are often used to spread misinformation. 🔍🚩

Finally, myth busters always read past the headlines, check the credibility of their sources, and consult more than one to get the full picture. 📚That’s why we’ve added multiple trusted sources!

Sound like you? Then welcome to the squad!

Share our original Bluesky Post!

We may be late to the trend, but it was too much fun 😅 Here's our myth-buster's starter pack! Featuring many exciting accessories that you can read more about here 👉 scienceupfirst.com/misinformati… Do you see yourself in our set? Welcome to the team! #ScienceUpFirst

— ScienceUpFirst (@scienceupfirst.bsky.social) May 2, 2025 at 10:38 AM

[image or embed]View our original Instagram Post!

-

The development of media truth discernment and fake news detection is related to the development of reasoning during adolescence

Increasing logical and reasoning capacity among youth will lead to better detection of fake and inaccurate news content over one’s lifetime.

Research focused on adolescents assessed truth discernment and the “illusory truth” effect, an effect which highlights how that increased exposures to fake information creates heightened impressions of accuracy.

Key findings include further evidence of the illusory truth effect and that increased reasoning abilities strengthens the ability to discern truth in media.

-

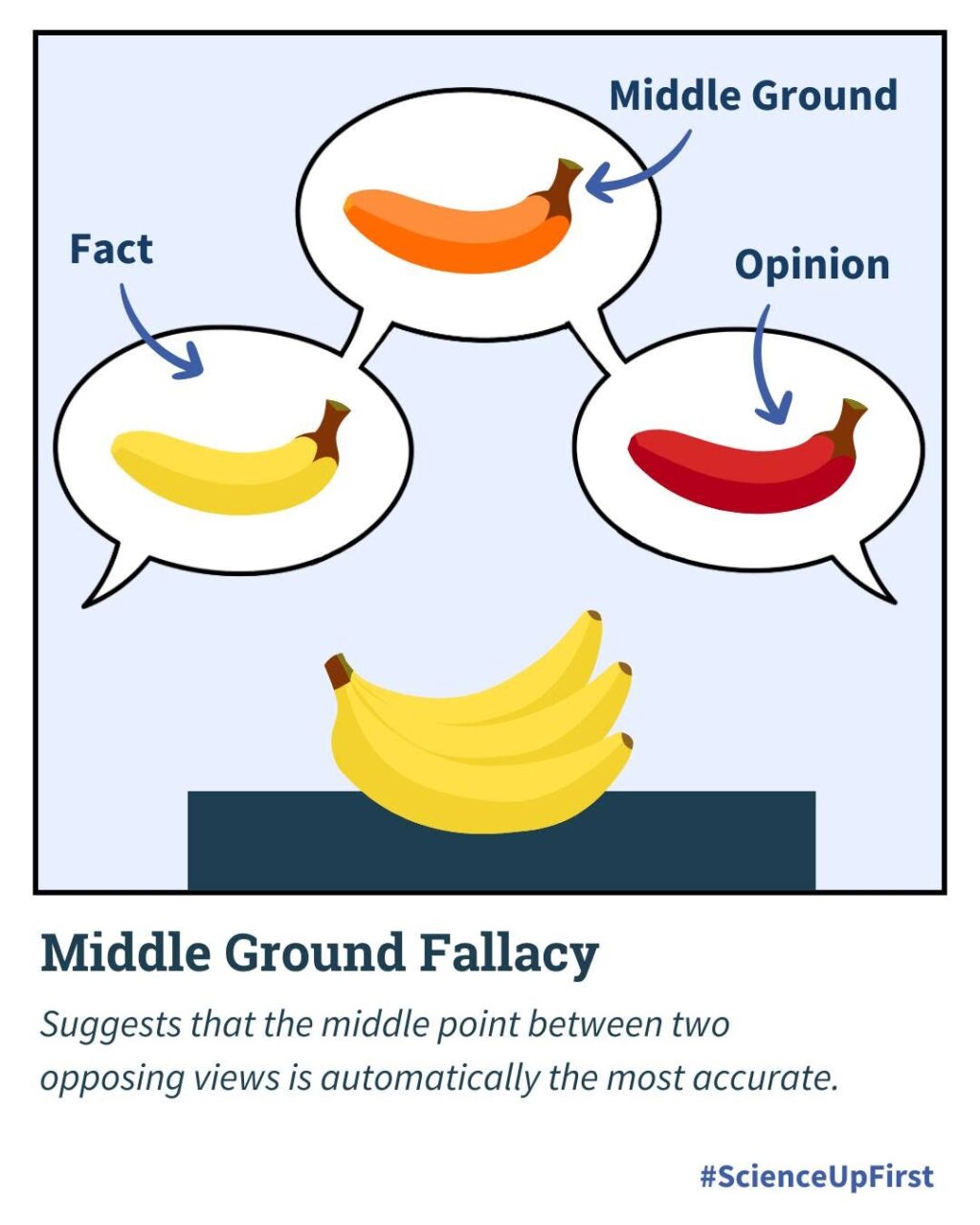

Middle Ground Fallacy

I say, bananas are yellow. You say, bananas are red. Can’t we compromise and just call them orange?

Here’s another example, let’s say two people argue about eating raw chicken. One says it can contain harmful bacteria and must be fully cooked. The other says it’s totally fine to eat raw. To settle the debate, they compromise by only cooking the chicken partially, so it’s still a little pink inside.

That’s the middle ground fallacy in action, and a salmonella special waiting to happen (1,2). Yikes!

Also called appeal to moderation, golden mean fallacy, or gray fallacy, this reasoning suggests that the middle point between two opposing views is automatically the most accurate (3,4,5,6). But truth isn’t decided by averaging opinions. If one of those extremes is clearly false, then the compromise isn’t a fair solution – it’s a distortion of the truth (3,7).

This fallacy is sneaky because it “feels” fair (8). But it’s misleading (2,4,5,7,8):

- It gives both arguments the same weight, even when only one is supported by science (read more about the false balance bias – 9). Raw chicken can carry harmful bacteria like Salmonella and Campylobacter, and the only way to kill it is by cooking the meat thoroughly.

- It assumes that the middle ground is always the best answer – but “a little pink” is still unsafe.

- It ignores the possibility that other, better solutions might exist.

- It can encourage people to present radical or false claims, hoping others will settle on a “reasonable” middle, which would still include misinformation.

Sometimes, finding a compromise is helpful. But when it comes to facts, “meeting in the middle” isn’t always the best – or the most accurate – solution (2,4,5,7,8).

To avoid falling for it (6):

- Ask: Is there evidence for both sides?

- Evaluate each claim on its own, not just where it sits on a spectrum.

- Remember: half-truths can still be harmful.

Truth isn’t always found halfway between two opinions. Sometimes, it’s firmly on one side.

Sources- Edzard Ernst: The “middle ground” fallacy | The BMJ | July 2012

- Poultry safety | Government of Canada | February 2019

- Middle ground | Your logical fallacy is

- Middle Ground – Definition & Examples | Logical Fallacies

- Argument to Moderation | Logically Fallacious

- What is The Middle Ground Fallacy? | Critical Thinking Basics – Psychology Corner

- The Problem with the Middle Ground | by Diana Van Dyke | Medium | March 2023

- Middle Ground – Bad Arguments | Wiley Online Library | May 2018

- False Balance Bias | ScienceUpFirst | September 2023

Share our original Bluesky post!

The truth isn't always found halfway between two opinions. Sometimes it's firmly on one side. Learn more about Middle Ground Fallacy here. 👉 scienceupfirst.com/misinformati… #ScienceUpFirst

— ScienceUpFirst (@scienceupfirst.bsky.social) April 17, 2025 at 4:19 PM

[image or embed]View our original Instagram Post!

-

Canadian Medical Association 2025 health and media annual tracking survey. 2nd edition

Survey of the Canadian population finds high presence of, and exposures to, misinformation online. More than 33% of Canadians report having avoided at least one effective treatment because of inaccurate information. Approximately 1 in 4 Canadians believe in the chemtrails conspiracy, that the mercury preservative in vaccines (thimerosal) could cause autism, and that 5G causes cancer.

-

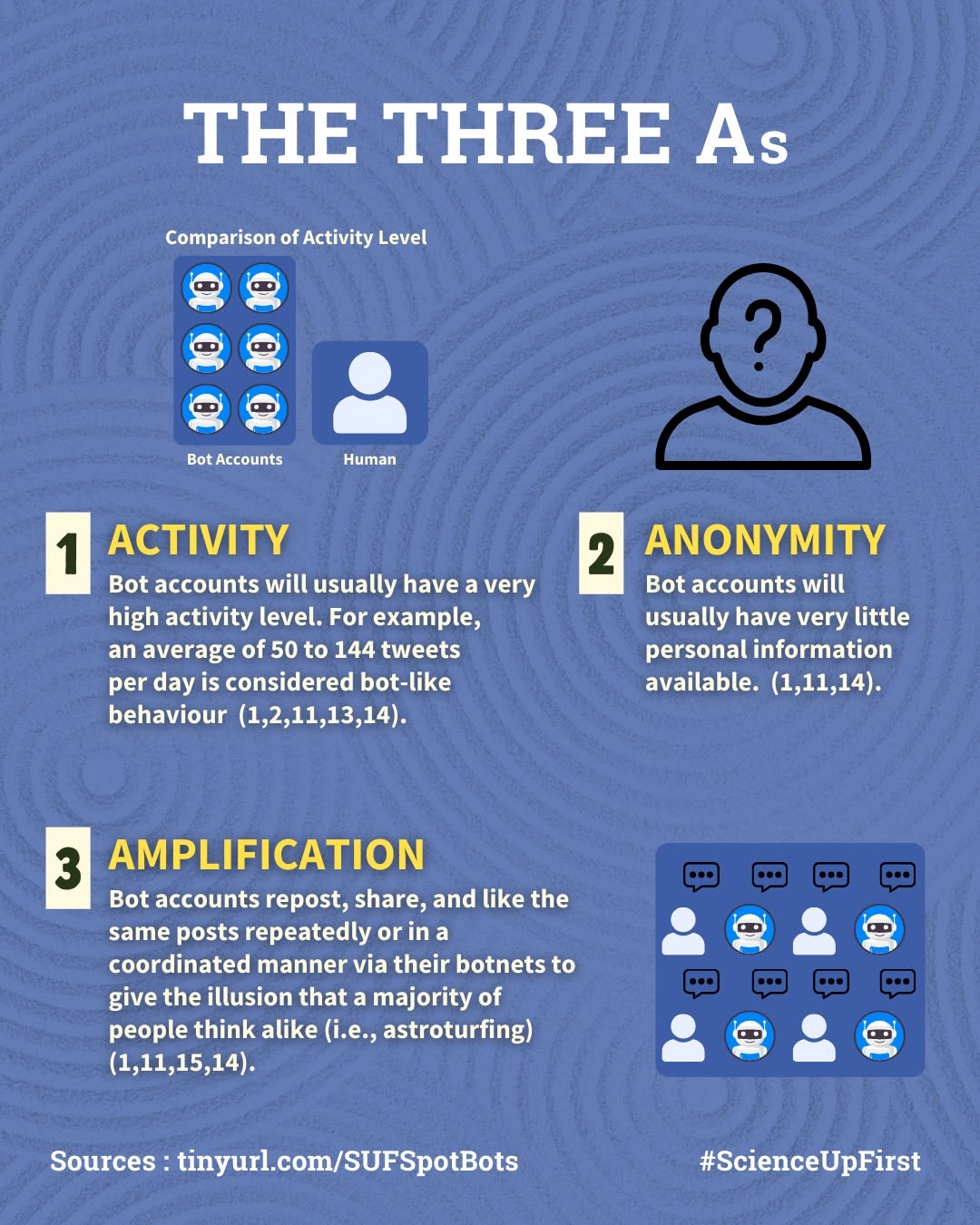

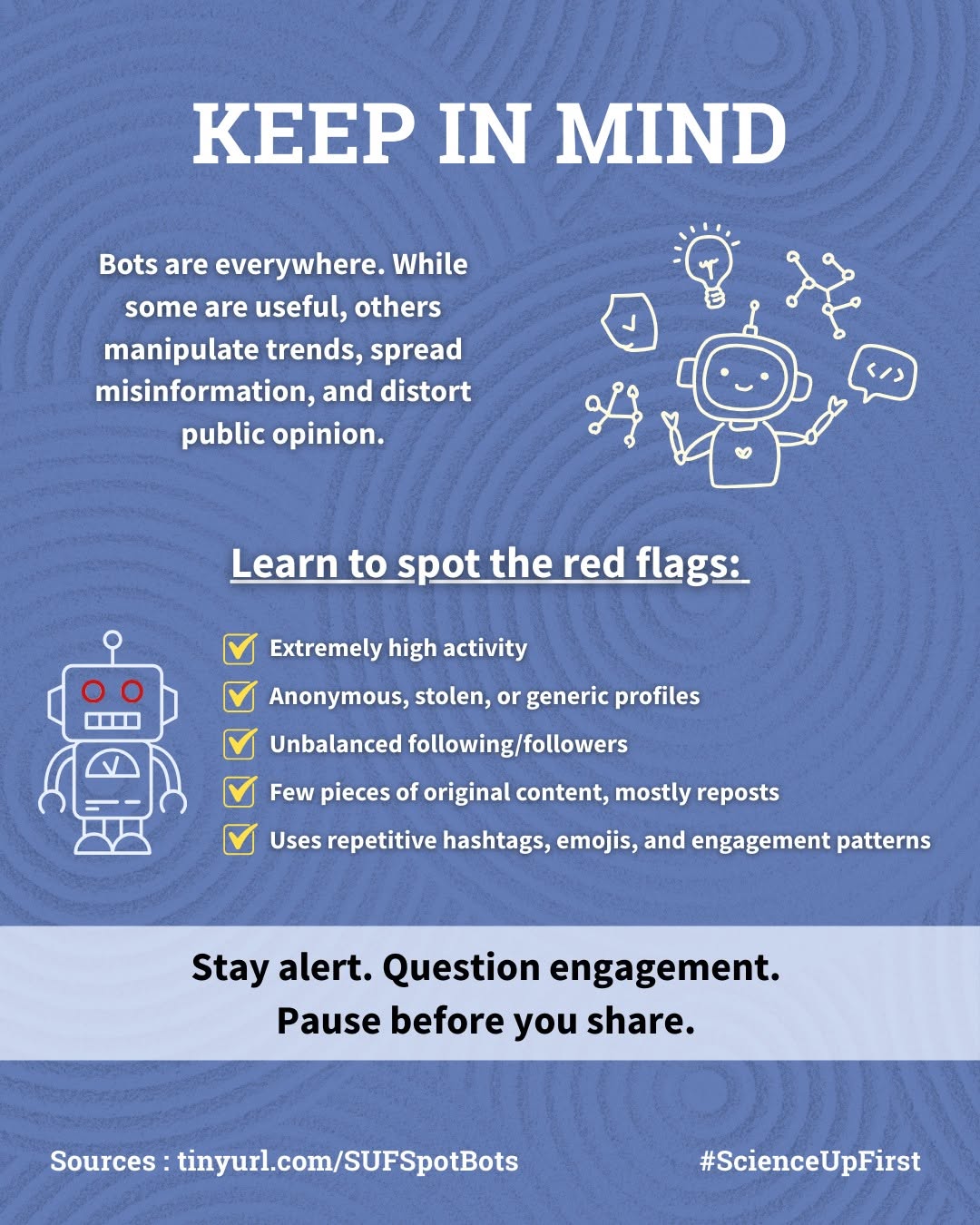

The Little Guide to Spotting Bots

Social Media Bots can be designed for different purposes (2,11,19):

- Click/Like Farming: Bots boost an account’s popularity by generating fake likes or reposts.

- Hashtag Highjacking: Bots use popular hashtags to spread spam or malicious content.

- Repost Storm: A lead bot shares content, triggering a coordinated reposting attack by a bot network.

- Trend Jacking: Bots exploit trending topics to spread their message or target an audience.

- Astroturfing: Bots can throw their weight behind different issues to artificially inflate the perception of support.

There are detection tools online that can help you identify X bot accounts (e.g. Bot-o-Meter, Twitter Audit, Bot Sentinel) (18).

If you think you have found a bot, report it and block it (20). By reporting bot accounts and removing them from your followers list, you can limit the spread of misinformation, but also potentially boost your account as engagement on your posts will now be more genuine (16).

Have you spotted bots in the wild? How did you know they were bot accounts? Let us know!

Sources- BotSpot: Twelve Ways to Spot a Bot | Digital Forensic Research Lab | August 2017

- Social Media Bots Overview | Homeland Security | May 2018

- Twitter Bots & Climate Disinformation | Scientific American | January 2021

- Social media, fake news, and polarization | Science Direct

- New Strategy to Detect Social Bots | Stonybrook University | November 2021

- Inside a Facebook Bot Farm | Comparitech | March 2022

- Nearly 48 million Twitter accounts could be bots | CNBC | March 2017

- Huge networks of fake accounts found on Twitter | BBC News | January 2017

- Battle of the Botnets | Digital Forensic Research Lab | July 2017

- Bots and Computational Propaganda | Cambridge University | August 2020

- Social Media Bots Infographic Set |The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

- Bots tried to influence the U.S. election | science.org | September 2017

- ‘Bots’ boost Russian backlash against Olympic ban | Reuters | December 2017

- Spotting Bots | TRADOC

- What Is ‘Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior’? | snopes.com | September 2021

- Snopes Tips: How to Spot Social Media Bots | snopes.com | July 2022

- How to spot fake social media accounts, bots and trolls dw.com |July 2022

- Media Literacy & Misinformation | Monmouth University

- Instagram Spam Bots | FraudBlocker.com

- The Ultimate Guide to Spotting and Fighting Bots on Social Media | BitDefender.com | July 2023

Share our original Bluesky Post!

Bots are everywhere. While some are useful, others manipulate trends, spread misinformation, and distort public opinion. How can you spot them? What can you do? Learn more 👉 scienceupfirst.com/misinformati… #ScienceUpFirst

— ScienceUpFirst (@scienceupfirst.bsky.social) April 4, 2025 at 10:26 AM

[image or embed]View our original Instagram Post!

-

Do you have depression? A summative content analysis of mental health-related content on TikTok

Analysis on the top 1000 TikTok videos with the hashtag #mentalhealth finds misleading content in 33.0% of videos containing advice or information. Videos with misleading content were viewed, liked, commented on, and shared more, on average, than videos with non-misleading content.